Author: Whitney Lisenbee

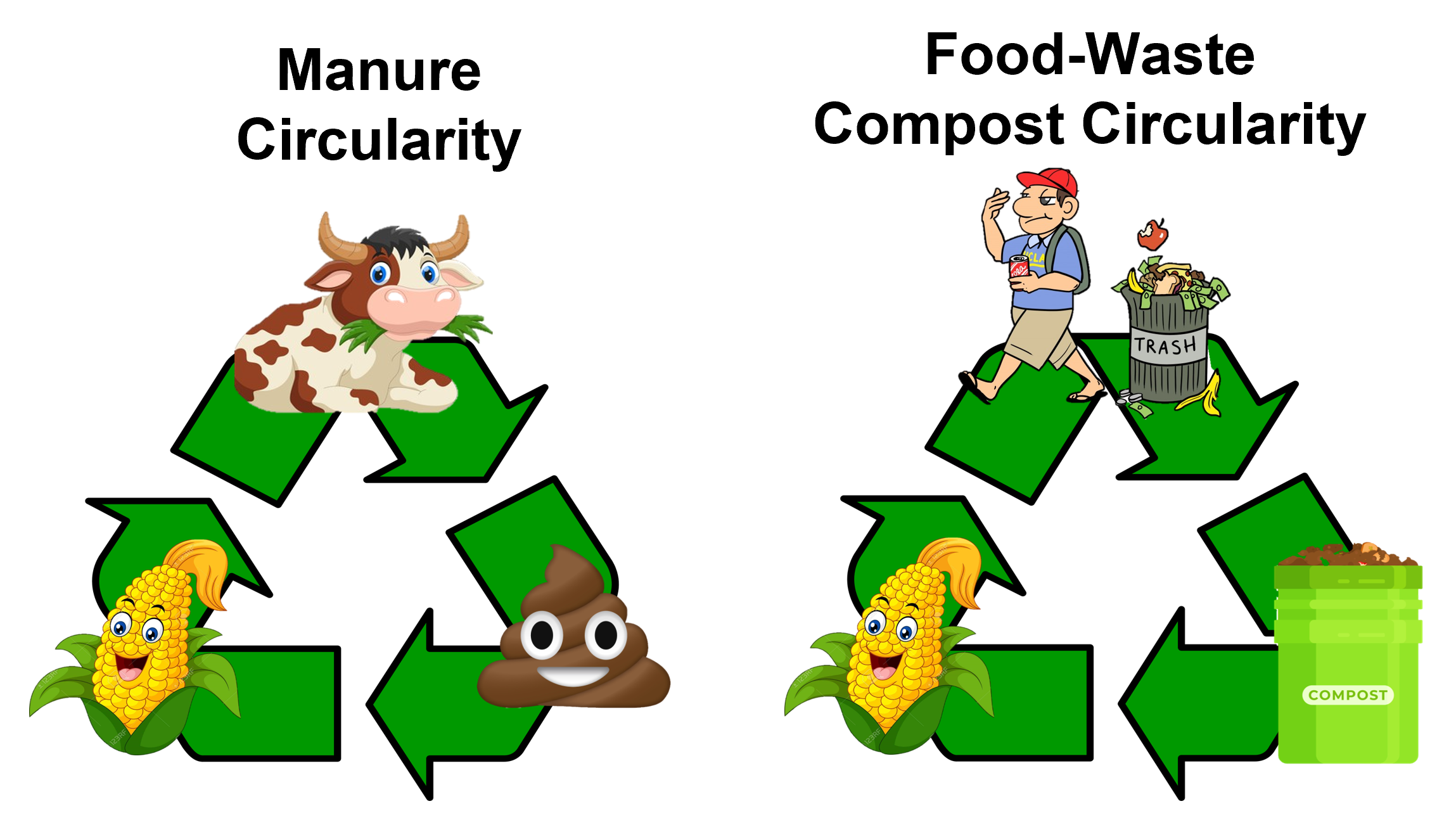

Circular systems have become a rising area of research in agriculture. The goal is to reduce and recycle waste streams for both environmental and economic benefits. In the agricultural regions of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, manure waste can be reutilized as a source of organic fertilizer for crops. Manure is currently constrained by transportation and storage limits but our study investigates what if manure could be transported further from the source? Is there enough cropland to utilize all the manure produced in the region?

Additionally, humans produce excess food waste that typically ends up in landfills where it produces significant greenhouse gas emissions. This waste could be composted to serve as another form of nutrients for cropland instead. We studied the production and application of food waste compost as an additional source of organic fertilizer along with manure.

We found that current manure production is applied to 16% of cropland in the Susquehanna River Basin, the largest agricultural watershed draining to the Chesapeake Bay. However, almost half of that is applied at levels higher than recommended due to transportation constraints. With improved transportation, 17% of cropland was able to apply manure at the recommended rate. Finally, food waste compost was able to double the amount of “circular” cropland by providing organic fertilizer to an additional 16% of cropland (for a total of 33%), typically in areas where manure was not available.

Circular agricultural strategies such as these provide many benefits e.g., reduced emissions, improved soil health, and reduced nutrient imports. However, we found that increased circularity could have a negative effect on water quality due to higher nitrogen application rates with organic fertilizers. Therefore, to continue decreasing nutrients reaching the Chesapeake Bay, nutrient-reducing conservation practices and nutrient management plans must accompany these circular agricultural practices.